My role

Research lead, working within a blended product team made up of US Digital Service and Ad Hoc researchers, designers, engineers, and product managers.

Activities

- Research recruiting

- Discussion guide preparation

- Pilot study

- Usability testing

- Research analysis

- Presentation

Will Veterans be successful using our MVP?

Our team had been working on vets.gov (which later became the new va.gov) to focus on providing services to Veterans and their families. The team had been delivering in a truly agile fashion – offering additional services and refining existing ones constantly.

In this case, the team planned to go live on the site with one specific kind of disability claim while other types would require users to go to other existing sites to complete. We wanted to know:

- Whether Veterans would be able to successfully self-select onto the correct path to make this type of claim

- Whether offering this set of functionality as a minimum viable product would be worthwhile or whether we should wait until other types of claims are available before launching

- How we could best help Veterans feel supported and eliminate confusion in their application process.

Recruiting Veterans requires rebuilding trust

I wrote up participant screening criteria, and our associate researcher took the lead in recruiting participants. It’s no small feat because unfortunately, Veterans are often the target of bad actors who claim to represent organizations that they don’t actually represent. With other populations (such as customers of an existing product), I rely more on email and automated scheduling tools. With Veterans, we relied heavily on phone calls. And in those phone calls, we had to work to establish trust and make it clear that we’re not asking anything from the participants except for their time and honest feedback. Sometimes it didn’t work. When it did work, people usually expressed a great deal of gratitude that the VA is acknowledging the issues Veterans face and actively seeking their feedback.

There is so much we want to know, but we only have so much time

Every Veteran we talked to had many stories: deaths and permanent injuries, PTSD, challenges with their transition to civilian life, and dealing with bureaucracy at the VA. All of this was important for myself and the team to know about so that the services we created could meet them where they were. We also wanted to make sure to get feedback on the key questions the team had for this project. I wrote a discussion guide that I followed with some flexibility. I included time notes in the section headings so that I could make an informed judgment about when to change the subject or skip a section, based on how the conversation is going.

I structured the sessions to begin with an interview and then do task-based usability testing using a clickable design prototype. In order to meet Veterans where they were and allow the team to deliver quickly, we conducted sessions remotely, using GoToMeeting.

User research as a team sport

I embrace user research as a team sport, so I encouraged team members to observe as many sessions as they could. I ran a pilot session internally and learned some adjustments to make to the prototype and the conversation guide. Teammates helped capture verbatim notes, and I asked everyone who observed to note their top takeaways at the end of every session.

Wrangling all the data

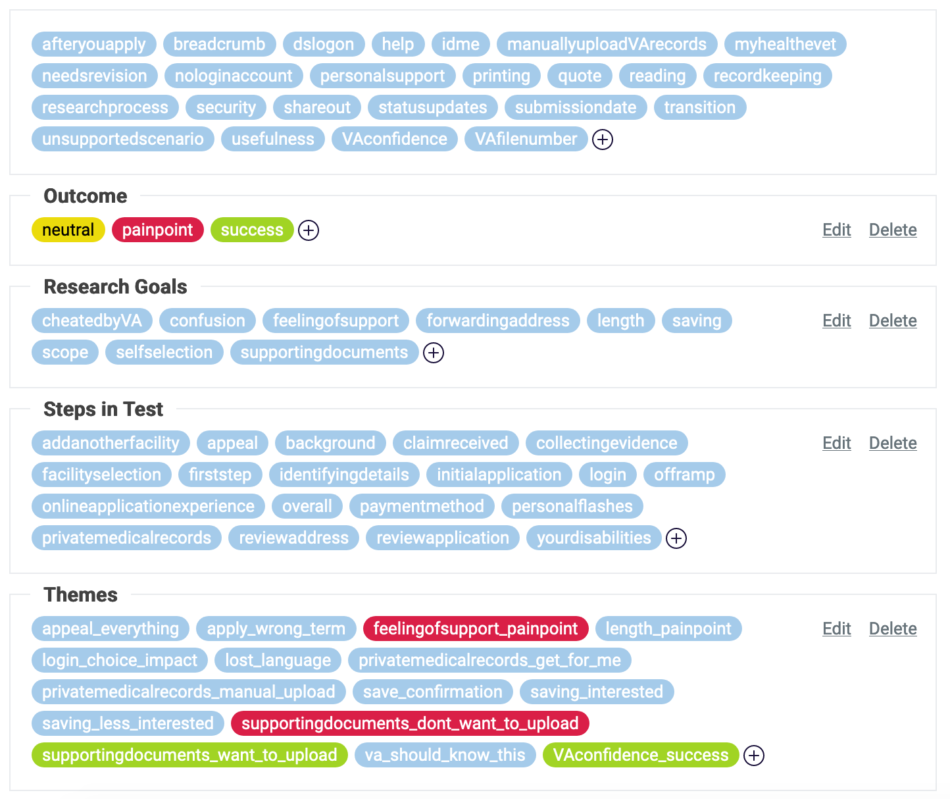

We conducted 6 sessions and captured about 20-30 observations per session, so in order to analyze it all, I led a fairly robust team process of analysis. We started by coding each observation with tags. I created a tagging guide so that the team could help with the workload and the result would be unified.

What does it all mean?

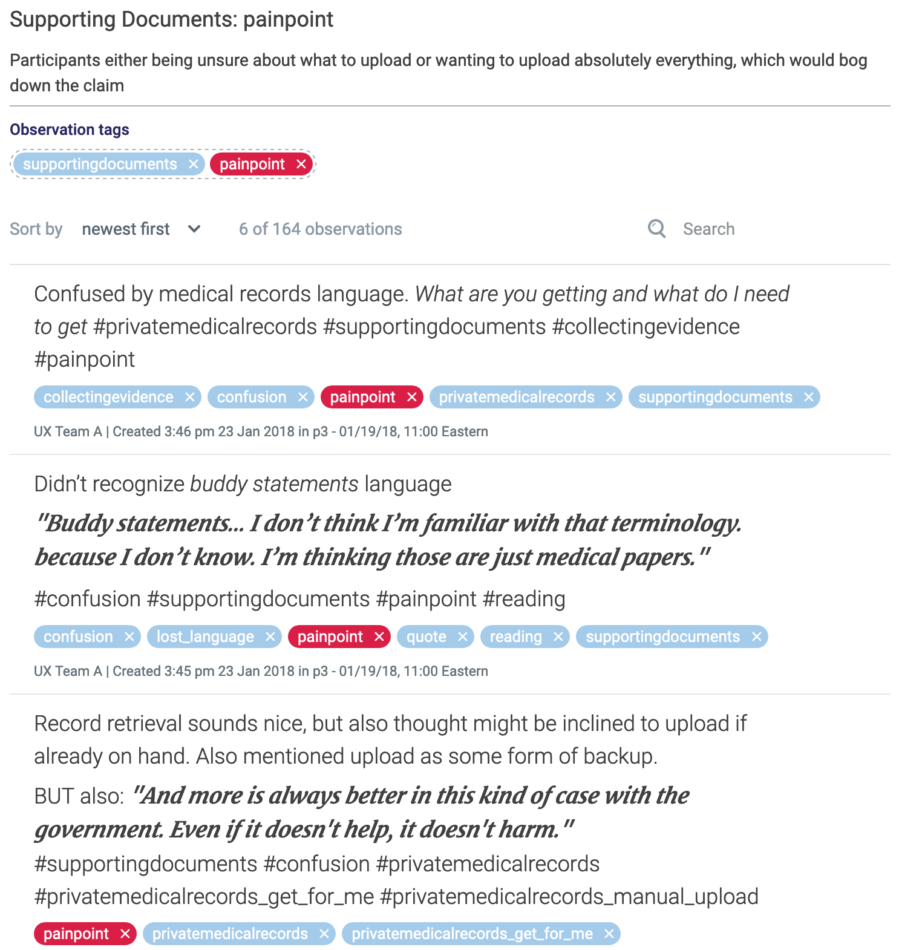

Once we tagged all the observations, we could easily pull out themes from a combination of tags. For example, we could find all the painpoints associated with the process of uploading supporting documents by filtering on observations that had both “painpoints” and “supporting documents” tags. We could also easily count how many users experienced any given issue.

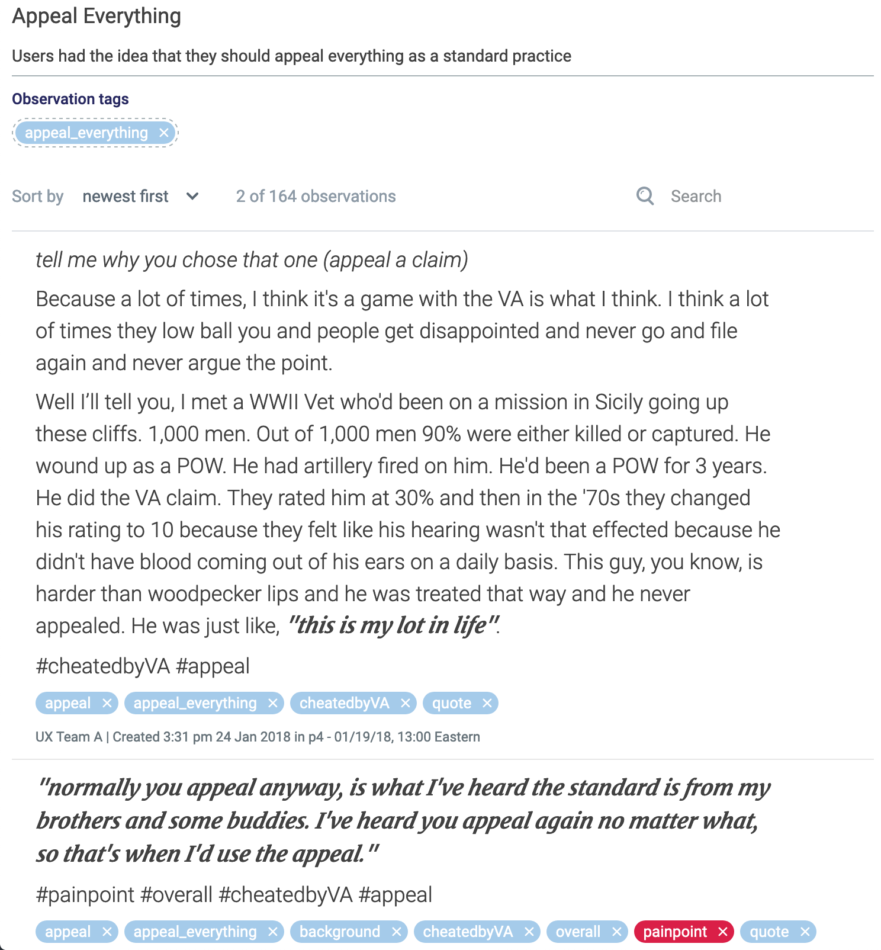

Once we isolated observations like that, we also found some other themes that stood out. As an example, some Veterans took an approach of appealing every decision by default.

The designed approach worked for most, and we learned some ways to make it better.

We found that 5/6 participants were able to get to the right place on their own and only 1/6 was frustrated with being redirected to another system in order to complete a different claim type. This validated that the designed approach was viable and gave the team confidence to move forward with the incremental launch.

We also learned some other nuances of Veterans’ experience with the design and provided some recommendations for the team to increase Veterans’ comfort levels and chance of success in applying for disability claims. Details in the report below.

Allowing Veterans to get the benefits they’ve earned

This feature and many others on the new site helped Veterans get access to their benefits in a central place rather than previously scattered locations that preceded it. In the fall of 2017, 302,000 Veterans applied for health benefits on the site. The US Digital Service tells more of the story in their Fall 2017 impact report.